Beyond Engagement: Credit Union Brand Love

Part Three of the Member Engagement Series

Dr. Katie Swanson, VP of Consumer Insight, Member Intelligence Group

As discussed in the previous two installments of this white paper series, member engagement is increasingly critical for the vitality of credit unions given today’s competitive and fractured financial services landscape. As differentiation becomes more difficult, however, even engagement with one’s members can prove to be insufficient. In this third of three white papers in the Engagement series, this issue is addressed through an evaluation of the concept of credit union brand love.

This white paper has three main objectives:

1) Provide background knowledge on brand love and why companies across industries are taking note of its potential power

2) Describe the development of the Credit Union Brand Love Score and report results of Member Intelligence Group’s (MIG) national research study on credit union brand love

3) Provide recommendations for credit unions interested in taking their member

relationships beyond engagement

Background

The concept of brand love has its roots in the studies of branding and consumer behavior and is found at the intersection of these two areas of research, as demonstrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Brand Love.

Branding

Initially, branding research focused on product brands, and several different conceptualizations of a brand emerged.

1) Brands as communicators – This common conceptualization positions the purpose of a brand as identifying the goods of a seller and differentiating them from others (Hankinson, 2004).

2) Brands as perceptual entities – This conceptualization centers on brand image and views a brand as connecting to consumers’ emotions, reasons, and senses (Hankinson, 2004).

3) Brands as value enhancers – In this conceptualization, the focus is on the value of a brand as a corporate asset in terms of brand equity, etc.

4) Brands as relationships – This conceptualization views brands as able to have personalities and relationships with consumers (Hankinson, 2004).

The first three of these conceptualizations approach branding from more of a “top down” perspective in that marketers view branding as something that they “do to” a product or with the goal of trying to control the brand (Medway, Swanson, Delpy-Neirotti, Pasquinelli, & Zenker, 2015). The fourth conceptualization, that of brands as relationships, however, takes a “bottom up” approach to branding. From this perspective, brands are viewed as emerging through co-creation with an organization’s consumers (Medway, et al., 2015). For organizations that are heavily dependent on service encounters, such as credit unions, the brands as relationships conceptualization is most appropriate.

Consumer Behavior

The second area of research from which brand love originates is consumer behavior. This

is an immense area of study, but for the purpose of this paper, the most relevant area of focus is that of consumer emotions and how those emotions impact behavior in terms of loyalty. Research indicates that consumers can experience a wide range of positive and negative emotions toward brands, including the basic-level emotion of love (Laros & Steenkamp, 2005). These emotions can impact consumers’ behavior in terms of their satisfaction response (Phillips & Baumgartner, 2002), their response to advertising (Holbrook & Batra, 1987), and their purchase behavior (Sherman & Mathur, 1997). All of this leads to a strong impact of emotions on consumers’ loyalty to brands.

There are various theories on the most effective way to conceptualize loyalty, but there is a general consensus that a multidimensional approach including both behavioral and attitudinal components is important (Velázquez, Saura, & Molina, 2011). It is well established that satisfaction alone does not necessarily lead to loyalty (Velázquez, et al., 2011), and traditional loyalty programs often fail because “loyalty” is defined purely in terms of behavior and repeat purchase to the exclusion of attitudinal components reflecting deeper emotional connection and personal involvement (Mattila, 2006). Consumers who repeatedly purchase a brand without attitudinal influences are said to have “spurious loyalty” or “inertia” (Dick & Basu, 1994, p. 101). “True” loyalty emerges only when both behavioral and attitudinal loyalty are present, as is the case when a consumer experiences brand love.

Brand Love

Since the early 1990s, businesses and academic institutions have studied relationship marketing and brand loyalty and have found that having two-way, meaningful relationships with consumers, and understanding their needs, can improve a company’s performance (Fournier & Avery 2011). However, as relationship-building practices have become more commonplace, brands have become increasingly homogenous, and it is difficult for a brand to stand out (Clancy, 2001). Credit unions are no exception to this and may be especially susceptible due to perceived homogeneity among financial services and products. Some select organizations, across different industries, have managed to form deep relationships with their consumers to the point where the consumers say they “love” the brand. When this happens, the consumer feels that the brand actually becomes part of his/her identity, and brand love is formed (Carroll & Ahuvia, 2006).

Consumers must be satisfied with a brand in order to experience brand love, but being satisfied does not necessarily lead to brand love and is insufficient on its own. Additionally, a consumer must believe in the quality of a brand before brand love develops (Batra, Ahuvia, & Bagozzi, 2012). When brand love is formed, and as it increases, consumers are more loyal to the brand in terms of repurchasing it and are more likely to engage in positive word-of-mouth, or tell others about it (Carroll & Ahuvia, 2006). They are also resistant to negative information about the brand and tend to discount others’ unfavorable comments (Batra et al., 2012). Furthermore, the love that consumers experience for a brand should be viewed in terms of a long-term relationship as opposed to a transient emotion, as that is how consumers experience it (Batra et. al, 2012). In fact, consumers’ level of emotional arousal for a loved brand decreases over time while their feelings that the brand is part of who they are increase over time (Reimann, Castaño, Zaichkowsky, & Bechara, 2012).

Brand love is characterized by six main categories (Batra et al., 2012):

Self-brand integration:

This is demonstrated when a brand is able to express a consumer’s actual and desired identities and to connect with life’s deeper meanings and important values.

Passion-driven behaviors:

A consumer demonstrates passion-driven behaviors by frequently interacting with a brand in the past and by having strong desires to use and invest resources in it.

Positive emotional connections:

These go beyond positive feelings and also include a consumer’s attachment to a brand and feelings of “rightness” about it and “fit” with it.

Long-term relationship:

This indicates that a consumer anticipates continuing a relationship with the brand into the future.

Anticipated separation distress:

This indicates a consumer’s anticipated feelings of anxiety and apprehension if a brand were to go away.

Attitude valence:

This reflects how strong a consumer’s feelings are about a brand.

While these categories identify how brand love can be defined and described, and how it is manifested, it is important to understand some of the antecedent conditions that lead up to the formation of brand love. As discussed earlier, perceived brand quality is one important condition (Batra et. al, 2012). In services settings specifically, trust in a brand; the extent to which the brand is responsive and caring; the extent to which consumers relate to a brand’s meaning and image; the brand’s uniqueness; the extent to which the brand provides a special, privileged experience; and the level of delight and pleasure consumers experience from the brand are all conditions that precede, and can lead to, the formation of brand love (Tsai, 2011). When brand love is formed, it, along with other factors such as the level of consumers’ commitment to the brand and the switching costs associated with the relationship, act as mediators which subsequently lead to positive results for the brand such as consumers repurchasing it, recommending it to others, and displaying overall loyalty (Tsai, 2011).

Development of the Credit Union Brand Love Score and MIG’s National Research

In order to research brand love in a credit union context, and to determine whether it is meaningful for credit unions to measure and monitor, the author of this white paper adapted (for the credit union industry) the brand love scale developed by Batra, et. al (2012). Using this adapted scale, the author of this white paper developed a Credit Union Brand Love Score which was used in a national research study conducted by Member Intelligence Group (MIG). Credit unions across the United States participated, and these organizations varied in asset size, charter type, and member demographics. In total, 6,788 complete responses were received, and a benchmark weighted average for credit union brand love was established. This benchmark, 59.6 (out of a possible 100), will be utilized going forward as a measure against which individual credit unions can compare their own brand love score.

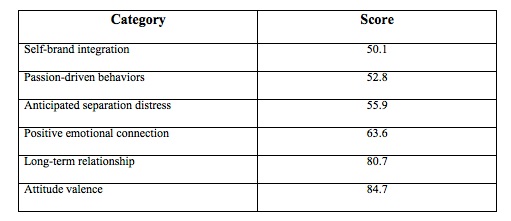

Scores for each of the six brand love categories were calculated as well and are as follows in Table 1 below:

Table 1. Brand Love Category Scores

As evident from Table 1, in general, it was most common for members to have positive overall feelings about their credit unions and anticipate having a relationship with those organizations for a long time. Less common were feelings that respondents’ credit unions had become part of who they are; passionate behaviors; and anticipated feelings of anxiety if respondents’ credit unions were to cease to exist. As average scores for the six different categories varied substantially, this presents an opportunity for the industry to focus on those areas with the lowest scores in an effort to increase overall brand love scores.

Brand love is positively correlated to favorable outcomes (loyalty, positive word-of-mouth, and resistance to others’ negative comments about the brand), and a belief in the quality of the brand is positively correlated to brand love. Interestingly, brand love has a stronger correlation to actually engaging in positive word-of-mouth (speaking favorably about the credit union to others) than NPS (which measures hypothetical willingness to speak favorably about the credit union).

Also, in general, individuals with lower income, and those who were older, reported stronger brand love for their credit unions than younger members and those with higher income. This is not surprising, as research in related fields, such as people’s attachments to places, has shown that demographic variables are relevant. For example, older individuals tend to have stronger attachments to places than younger individuals (Hidalgo & Hernández, 2001). Additionally, members who utilized more credit union products (such as credit cards, checking accounts, and mortgages) tended to have higher brand love scores than those without those products. Furthermore, those with a preference for opening accounts and applying for loans in the branch (as opposed to online, over the phone, etc.) reported higher levels of brand love.

Brand love for credit unions is positively correlated to NPS, but the correlation is only moderate in strength. In other words, the two are related, complementary measures. It is important to measure both, as they are providing distinct, yet complementary, insights. As discussed in the first two white papers in the Engagement series, NPS provides a transient gauge of member sentiments, but it is difficult to know how an organization can improve that score. Brand love, however, is not transient, and there are actionable insights that emerge from measuring it, as discussed below.

The results of the survey also demonstrated that high-performing credit unions tended to greatly exceed the others in three particular areas: having a passionate desire to use the credit union, feeling a strong emotional connection and attachment to the credit union, and feeling a natural fit with the credit union.

Furthermore, preliminarily, results of the research indicate a strong, positive correlation between a credit union’s brand love score and its return on assets. This requires additional research and will be measured in future studies, as further validation of this relationship could provide valuable and actionable insight for credit unions regarding their profitability.

Recommendations

In light of the research results described above, it is recommended that credit union leadership consider the following:

1) Research and Track Brand Love – As discussed in the second paper in this Engagement white paper series, it is important to take a variety of engagement measures into account when evaluating a credit union’s level of member engagement. As this white paper indicates, however, even engagement is often insufficient. Respondents to the national brand love survey demonstrated that love for a credit union is possible and results in favorable outcomes for the credit union. For example, brand love had a stronger correlation to actually promoting the credit union than NPS. Continue to track your members’ engagement with your institution, and add the credit union brand love score as a complementary measure in order to evaluate deeper emotional connections. As love is an emotion, and over-reliance on quantitative measures alone can result in incomplete understanding of emotions (Roberts, 2005), consider qualitative research as well.

2) Get Members Involved with the Credit Union – Respondents to the national brand love survey who had more products with the credit union, as well as those who preferred opening accounts and applying for loans in the branch, had higher brand love scores. These individuals are more involved with their credit unions and are subsequently feeling deeper attachments and feelings of love. Try to get others to emulate this behavior by encouraging additional products and reminding members of opportunities to visit a branch or consult with a representative via a virtual meeting.

3) Focus on Key Areas to Foster Brand Love – As the credit unions with the highest brand love scores tended to particularly excel in the areas of members having a passionate desire to use the credit union, feeling a strong emotional connection and attachment to the credit union, and feeling a natural fit with the credit union, consider ways to grow in these areas. Think about ways that the credit union’s values coincide with individual members’ values, and use storytelling to communicate those values to your members. As they develop deeper emotional connections with your organization through shared values, their desire to do business with you will grow. Ultimately, they will reward you with deeper love and more business.

For more ideas on ways you can implement brand love research for your organization, contact Katie Swanson at [email protected]. Please stay tuned for future white papers from Member Intelligence Group.

References

Batra, R., Ahuvia, A., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2012). Brand love. Journal of Marketing, 76(March), 1-16.

Carroll, B. A., & Ahuvia, A. C. (2006). Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Marketing Letters, 17(2), 79-89.

Clancy, K. J. (2001). Save America’s dying brands. Marketing Management, 10(3), 36-41.

Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2), 99-113.

Fournier, S., & Avery, J. (2011). Putting the ‘relationship’ back into CRM. MIT Sloan Management Review, 52(3), 63-72.

Hankinson, G. (2004). Relational network brands: Towards a conceptual model of place brands. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10(2), 109-121.

Hidalgo, M. C., & Hernández, B. (2001). Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21, 273-281.

Holbrook, M. B., & Batra, R. (1987). Assessing the role of emotions as mediators of consumer responses to advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(December), 404-420.

Laros, F. J. M., & Steenkamp, J. E. M. (2005). Emotions in consumer behavior: A hierarchical approach. Journal of Business Research, 58, 1437-1445.

Mattila, A. S. (2006). How affective commitment boosts guest loyalty (and promotes frequent-guest programs). Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 47(2), 174-181.

Medway, D., Swanson, K., Delpy-Neirotti, L., Pasquinelli, C., & Zenker, S. (2015). Place branding: Are we wasting our time? Report of an AMA special session. Journal of Place Management & Development, 8(1), 63-68.

Phillips, D. M., & Baumgartner, H. (2002). The role of consumption emotions in the satisfaction response. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12(3), 243-252.

Roberts, K. (2005). lovemarks: the future beyond brands. Retrieved from http://www.amazon.com.

Sherman, E., & Mathur, A. (1997). Store environment and consumer purchase behavior: Mediating role of consumer emotions. Psychology & Marketing, 14(4), 361-378.

Tsai, S. (2011). Strategic relationship management and service brand marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 45(7/8), 1194-1213.

Velázquez, B. M., Saura, I. G., & Molina, M. E. R. (2011). Conceptualizing and measuring loyalty: Towards a conceptual model of tourist loyalty antecedents. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 17(1), 65-81.